OKS-lab fragt…

|

In der Serie »OKS-lab fragt…« beantworten Dozenten, Fotografen, Macher und Absolventen im Rahmen der Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie Fragen zu ihrer Arbeit, ihrer Beziehung zur Fotografie und Lebensart. Ein Gespräch (*auf Englisch) mit: Michael Grieve, Gastdozent an der Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie

You are living between two very different cities: Athens and Berlin. There is a rumour going around that Athens is becoming the new European inspiring capital of art happenings. In your opinion, what is so special about Athens and what makes it so interesting to work there at the moment? How do you feel there? I like the contrast between these two very different cities and this will perhaps lead to an as yet undetermined synergy. What’s exciting about Athens is that it is not yet gentrified. It is a very vibrant and frenetic city with strong traditions. Geographically it’s also very interesting, situated at the very edge of Europe and is a conflation of the Middle Eastern and European cultures. For me, as an observer, it has a strange and intriguing dichotomy. And everywhere you look there is the ancient reminder that this was the beginning of western thinking and political organisation. Athens, therefore, is a constant reminder of the artistic, scientific and intellectual culture that we inhabit and often take for granted. Essentially I enjoy both cities but the appeal to Athens is that it has an edge to it. It’s a personal choice and is part of the on going narrative I have with myself, this adventure of life. Plus it gives me space to experience and do the work I want to do as a consequence of that experience. But also dig into my archive of work stretching back 30 years from assignments I did to personal projects. By comparison Berlin is rapidly becoming a very conformist city, which was inevitable. The spill over from expensive cities like London and Paris has meant a mass influx of those wanting to live the ‚artist‘ life style. And so the authenticity of the city has been eroded towards the predictability of coffee shops and trendy art. Essentially western cultures have become self-conscious, making spontaneity a harder attitude to live by. Until 8 years ago I had lived in London for 23 years and experienced first hand the vacuous expansion of a superficial gentrification. London has always been a very particular city of change and fluidity, charged with the energy of light and dark, and this was always the major essence of London’s personality. London in 1990 is certainly not the London of today but neither is the mentality of the new occupants. But I cannot let go of Berlin. It is a city still rich in atmosphere and energy and for sure was the most amazing place for possibilities, and even if those possibilities are getting harder due to money and over saturation of so called art, it still offers far more potential than the bland and comfortable situations to be found elsewhere. Though in Berlin everyone seems to struggle to find a place, whereas in Athens you can still feel the potential of available space. Let’s see what happens. I cannot pretend to understand economic, political and cultural situation of Greece but certainly it is complicated. Greeks are really trying to pull out of their problems and everyone, as far as I can make out, feels it. Since moving there I’ve begun to feel a sense of the responsibility towards understanding the Greek political and economic situation and the thirst for new forms of culture. It may sound like a total cliché, but the culture scene is a heartbeat of every society. There is little money for the arts and therefore the country is certainly deprived of a blossoming contemporary art culture despite the efforts of galleries, curators and artists. But for sure the mood is changing and I can see the will and determinism of individuals to make Athens work. It is crucial to understand the traditions and temperament of the place and people, and not bombastically barge in. I say this as an outsider. So, it’s an exciting time to be in such a metropolis.

In your work ‚The Foriegner (sic)‘ you explore the subjective experience of your life and of being a foreigner yourself. In what ways has travelling around the world and being based in different countries influenced your photography? The Foriegner [sic] is more about being foreign to myself. There is a point in life when you cannot escape yourself and so the need is to confront yourself. And as I entered my middle years I also understood that movement is the life. Rather than living a more comfortable, and hence stagnant, life in London I wanted to explore a greater sense of the inner experience via the outer experience and this involves risk, change and instability. I also needed to work on myself to better understand and integrate what the psychoanalyst Carl Jung describes as the ’shadow side‘ of my personality. My endeavour was to photograph in a free manner away from the constraints of making a ‚project‘, to embark on a body of work that manifested itself from a psychological bearing. The political is less interesting to me, but individual self-understanding is paramount and the root of everything we do. I stopped working professionally as a photographer in 2011. The last commissioned work that I did was about riots that happened in various cities in England, for the French newspaper Le Monde. And although my life in London certainly had its challenges I was afraid of stewing in the persona I had constructed for myself. It was time to move on. At this point Michael points out his life motto which he follows also in his photographic work: „Uncertainty was the only thing that I wanted to be certain of. Once I understood this I embarked upon a journey but also came to understand that I needed to mediate between order and chaos to maintain that journey as something fruitful. But like any journey there is always the unpredictable; loss, love, desire, longing and danger alter the course of life and this obviously is the true nature of a journey, because this is life, and a deterministic attitude is subject to the immensity of life. I was at liberty to photograph what I wanted and what I wanted to do was something non-specific, something without a defining concept. My working process was no longer the same as before. Just to follow the course of my life and try to understand through just being. I wanted to explore myself and photography was a part of that process. What became apparent is that I would photograph instinctively certain phenomena of what is ‚there‘ in reality, that in some way I was compelled towards. The vague notion I had in my head is that the work produced would be semi-autobiographical, in the sense that it is a fiction based on my reality, but that I am some kind of unseen protagonist in the story. The photographs have an uncanny character. To some extent the sensibility of the photographs is of more value than what is actually photographed. Titles are important to me, they act as an anchor so that I do not drift to far away from the core of the meaning of what I am trying to do. The Foriegner (sic) is a title that has been spelt wrong and so sic, meaning thus, from the Latin abverb sicerat scriptum (thus as was written), denotes the deliberate mistake of the ie in foreigner. It relates also to the ie in my surname. And so, to some extent, the title of the work contains the meaning of the work produced. You have taken a number of portraits in your career, and as you once said in an interview: „portrait photography is deceptively complex“. What do you think makes you such a good portrait photographer?

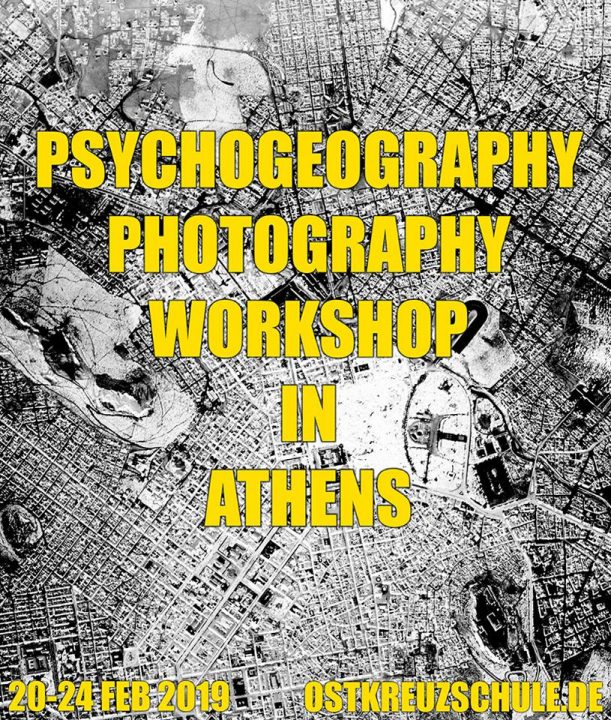

When I worked for magazines I did a lot of portraits and so I learnt how to work quickly and deal with what is ‚there‘ and to look at the potential of a portrait by developing my observational skills, subject, form, colour, tones, light, shadow, atmosphere, (thinks about it for a longer time). You know, just keep it simple! Meaning also that I had no time to overthink but to shoot instinctively with a serious intent but in a casual manner. Sometimes it can be quite difficult to relate to someone that you’re taking the portrait of. You can’t quite capture the essence of that person. I mean, you can still follow the basic rules of a good portrait, but that is not what makes a good portrait photographer. One example is my portrait of Antoine d’Agata.

That portrait was a release of a moment and it was just a conversation with him. I saw a certain light and said to him that he should stand up into the light, and so I got it, and then we sat down and continued the conversation. So you need to be vigilant for the right possibility. A portrait is a way to connect with another person and so I think it’s important to show something of that connection and to reveal in a subtle way what they are and what they do without showing what they do. But at the same time the portrait is a description of a person; it’s a description of how they look, and that can be variable. I mean we look different in the morning than in the evening… and we are shaped and formed by the light. Light also changes meaning. Those are the tools that I use. It’s the philosophy ‚lets go with the flow‘ and trust yourself whilst doing it. I am also in this idea of a psychological portrait with the strong belief that the person in front of me is enough. I always feel a great sense of responsibility towards the subject as I realised that it is a matter of trust and mutual respect. For the past seven years I have worked as a regular writer for the British Journal of Photography and I am in the unique position where not only do I write the feature but also shoot a portrait of the photographer, and believe me it takes a lot of confidence to photograph other photographers!  Michael taking photos of Boris Mikhailov and Vita Photo: Karolina Spolniewski What is your relationship with Ostkreuz School and what are you looking forward to in teaching your seminar at the Ostkreuzschule for Photography? The first exhibition I encountered when I moved to Berlin five years ago, was an undergraduate exhibition from the Ostkreuz School. That year the exhibition was near Janowitzbrucke in a disused supermarket. I was surprised first of all by the amount of people that attended, and then by the consistency and strength of the work. I became more intrigued by Ostkreuz. You can imagine as a non-German, British photographer, I had little idea what kind of tradition the school had and with time I learned more and actually wrote a feature about the school for the British Journal of Photography. But my initial reaction when seeing that first exhibition was that I would like to teach there. And so, five years later, here I am. And very honoured to be part of an educational establishment that has integrity and strength of character. I really appreciate Werner and Thomas for having faith in my abilities. I am teaching seminars once a month that are one-day sessions so I take this limited time seriously by keeping the continuity alive. The results are important, but at this point it’s so much more about the process. Creative output comes with being smart, conscientious and strong willed. But failing and learning from mistakes is part of the process and I encourage students to question themselves. With many experiences of workshops and lecturing at schools what do you think makes a good young photographer nowadays? A good photographer is someone who is fuelled by a passion for life in spite of the odds. This passion will take him or her on an adventure. You have to fully embrace the experience of living. Photography is a skill you may master but will never understand, but what it can potentially do is bring you closer to your reality. So, be open, take risks and sail the sea of uncertainty. And the work that shines through is not necessarily the cleverest, and certainly not the most perfect, as this kind of work becomes clinical, but the work that has integrity and life and that comes from blood, sweat and tears. Surely the most important element is believability. In 2016 you founded Berlin Foto Kiez, which grew into an important part of Berlin’s photo scene. How would you describe Berlin’s photo scene in a couple of words? To understand that is to make a distinction between the trendy photography, which is in abundance in Berlin, and the serious work. Photography is easy, that’s what makes it difficult. All to often I go to exhibitions and it often seems that how you look is more important than what’s hanging on the walls. A lot of what I have seen is a bit half-baked. It’s a bit to easy to stick your photographs on a wall! Therefore it’s important to keep making work with substance. But you know there is serious work happening in Berlin and for sure I have met great artists and curators who are based here such as Thomas Weski, Thomas Struth and Arwed Messmer. And it is without doubt that photography in Berlin has a very strong history which is one of the reasons I moved here. What are you working on right now besides teaching and writing. Are there any interesting new photo series‘ we could see soon? With ‚Berlin Foto Kiez‘ I’m putting together a one-year workshop that will take place in three European cities, namely Berlin, Athens and Budapest. It will be with three different photographers who are yet to be announced. I am also cooking up other workshops on the Greek islands and a workshop in a French chateau with Roger Ballen and Brad Feuerhelm from American Suburb X. I am also working on a project called The Problem is the Answer which is a continuation of The Foriegner [sic], and so I am editing this now in Athens. It reflects my state of mind while living in Berlin and is more abstract in tone than The Foriegner [sic]. And since moving to Athens I have started something new that is based on a road running from Athens to Eleusis, situated 20 km from Athens. It is a road that was once a sacred way to mysterious rituals that happened during the ancient times. And so I am following the apparition of a very faint trace of something past, while describing the present. And I have organised an Ostkreuzschule workshop in Athens using psychogeography to navigate the city in unconventional ways. Thank you for your time Michael!

Michael Grieve is a British photographer currently based in Berlin. His photography explores the inner and outer landscapes of human connection. These documentary fictions, where the sensibility defines meaning, chronicle the journey of lived and unknown experience, bringing fragmented images together as narratives. He studied a BA in Film, Video & Photographic Arts at the Polytechnic of Central London and in 1997 graduated from the Photographic Studies MA at the University of Westminster. He then proceeded to work on commissions for diverse publications worldwide as a photojournalist and portrait photographer. For five years he was the deputy editor for ‚1000 Words‘ contemporary photography magazine. He was a senior lecturer of photography at Nottingham Trent University teaching theory and practice, and a lecturer at the Akademia Fotografii in Warsaw and Krakow and was also a lecturer teaching Documentary Photography and The History of Photography at Berliner Technische Kunsthochschule in Berlin. Michael teaches workshops on a regular basis and is currently a lecturer at Ostkreuzschule in Berlin. He sits on the steering committee for The International Interdisciplinary Institute (The Triple-I) in Rome, Regularly contributes as a writer and photographer for the British Journal of Photography and is the Founder and director of Berlin Foto Kiez International Photography Workshops based here in Berlin. Fotos: Michael Grieve.

|